On the Paintings Gallery of New South Wales, unfold all through 4 rooms on the underside floor of the first setting up, sits Nusra Latif Qureshi’s first major solo exhibition, Birds in Far Pavilions.

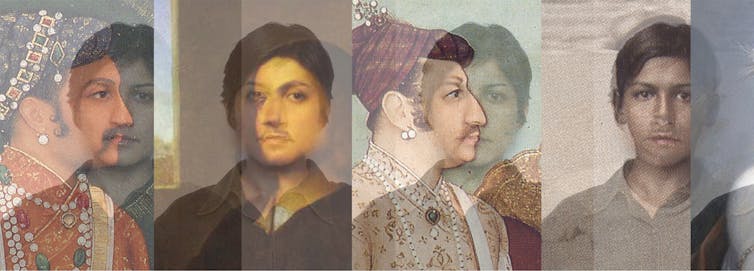

The exhibition is launched with Did you come proper right here to go looking out historic previous?a digital print Qureshi created in 2009 for the 53rd Venice Biennale.

The print is 9 metres large and choices 17 Mughal and Venetian work overlaid with Qureshi’s private passport {{photograph}}. The work responds on to city of Venice – and historic previous itself – as an “imagined land”.

Positioned like a marquee major in route of the current’s inside, it suggests the exhibition asks this question, too. Did you come proper right here to go looking out historic previous? The inquiry, Qureshi explains, refers partially to “the connection of artist with art work historic previous”.

That the exhibition performs with scale is turning into for an artist who was expert in not twoor Mughal miniature painting, on the Nationwide School of Arts in Lahore, Pakistan.

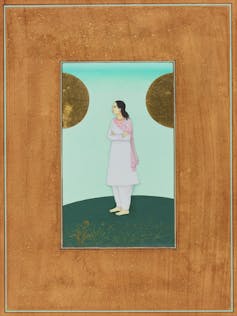

In Descriptions of earlier II (2001), golden crops sway beneath a woman’s toes.

You’d need a magnifying glass to grasp the blades of grass rising from the underside like gadgets of hair, rendered as finely because the woman’s private wavy strands.

An arrange on the far wall inside the first room, Shafts in flooring (2015), combines maps of the Costerfield antimony mines in Victoria with some regularly wares from a prospector’s camp.

In Qureshi’s arms, the room, with its yawning ceilings and empty centre, toys with its private sparseness. Friends are compelled to hew close to the works alongside the partitions, skimming the edges as if in orbit of nothing. Such is Qureshi’s and curator Matt Cox’s command of the home.

The choice befits how the artist toggles with home in her works, which usually fill the boards on which they’re rendered, and at totally different cases yield to swathes of coloured flooring.

Qureshi moved to Melbourne from Lahore in 2001 – from one former metropolis of the British empire to a special. This colonial comparability undergirds, nonetheless does not determine, her subsequent works.

On the exhibition’s coronary coronary heart is the Museum of misplaced recollections (2024), whereby Qureshi has gathered objects from the Paintings Gallery’s assortment, the Powerhouse Museum and her private studio.

In quite a lot of crowded present circumstances, she has positioned Australian souvenirs, Mughal work, photos, polo mallets and Indian daggers. Objects that speak to the museum’s encyclopaedic remit flip to converse with these from Qureshi’s private studio – a doily, a stone Bodhisattva, a textile, a plastic tank.

Throughout the nineteenth century, not two painters repurposed their experience and began hand-colouring photos. An earlier label tells us one {{photograph}}’s matter, embellished in deep blue, is a Shia Muslim from Sindh.

Leaning into the earlier

Qureshi’s work is as quite a bit art work because it’s art work historic previous. Historic previous and, by extension, historic art work, seem to have flip into harmful objects in Australia.

Perhaps to answer the neoliberal faculty’s obsession with KPIs, along with the Australian authorities’s “job-ready” protection, art work historic previous has turned to the present to proclaim its relevance. Curators and artists present imagined futures and reparative gambits that obscure or sit alongside historic supplies.

These interventions are important, however when they are not matched by a rigorous and nuanced engagement with historic previous, then historic objects flip into the tarnished relics of a benighted earlier. Relatedly, fashionable works flip into flattened into one or one different important posture.

This progressivist imaginative and prescient of historic previous makes a villain of the earlier and a hero of the present.

Nonetheless there usually are not any good heroes or villains in Qureshi’s works. Or, if there are, they’re strikingly adjoining – and solely two amongst many strands of an ever-unfolding historic previous.

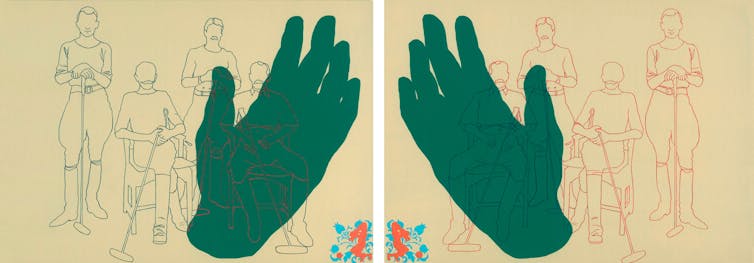

Her work are typically described for his or her layered outcomes. In Justified behavioural sketch (2002), the carmine outlines of British army officers with polo mallets resemble the rugged boundaries of maps as they invade a woman’s face.

This related outline sorts the third diptych inside the Achieved missions assortment (2012), proper right here barely coated by an open, inexperienced hand.

In Gardens of Want (2002), a botanical drawing from Scottish illustrator Sydney Parkinson is laid gently over Radha and her lover, the god Krishna.

From layers to threads

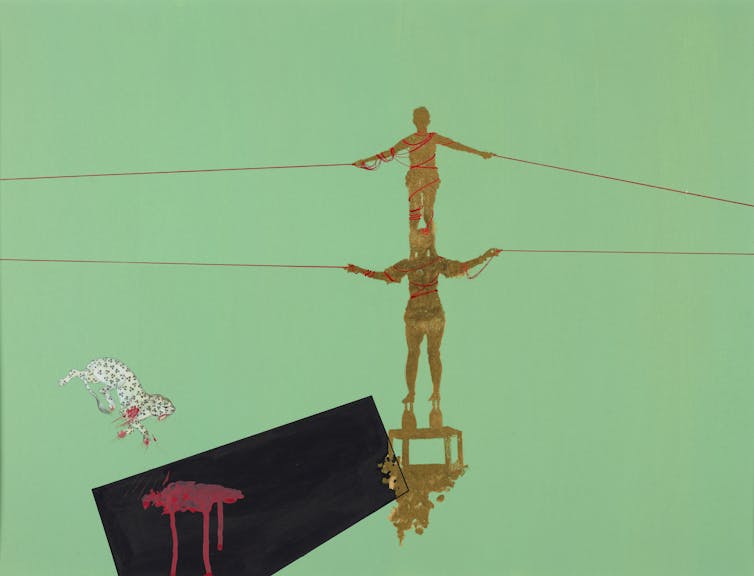

Over time, nonetheless, Qureshi’s layered traces have turned to string. Threads are animate and wayward, limp and tangled, inside the Conference of birds assortment (2013). The equivalent gossamer strings envelop and stabilise two acrobats in On the edges of darkness II (2016).

Further these days, these strings have been launched into the world. We see them draped above and via Qureshi’s work of nineteenth and early twentieth century portrait photos from Melbourne in Refined portraits of want (2018).

Crimson yarn spills from ringlet curls and feathered hats, connecting the oval work on the wall to not less than one one different and to corresponding works on a desk beneath.

Throughout the Museum of misplaced recollections, bits of string and wire drape and adjoin objects like crimson, deflated roads. And in The room with crimson tiles (2023) – pictured inside the header image above – arms acquire and go cascading thread down the dimensions of a inexperienced flooring.

Qureshi is pulling on points that can on no account untangle, nonetheless it is the pulling that points. Her art work attracts collectively objects and photos that resist choice – looping the present proper right into a earlier that continues to unravel.

In her work, we’re certain to the earlier and to not less than one one different with gadgets of scattered threads, should we choose to adjust to them.